Broad and sweeping, yet detailed and penetrating, Clay Shirky’s volume “Here Come’s Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations” is a tour de force of how technology influences group activity and organisation. Shirky skillfully blended social sciences like psychology, sociology and anthropology with elements of the social web – mailing lists, forums, blogs, Youtube, Flickr, MySpace, Facebook, Wikipedia and Twitter.

Weaving his words into an easily digestible narrative, Shirky isn’t afraid to borrow theories and concepts to back up his claims. A notable example is the Coasean Theory, which states that high transaction costs make hierarchical organisations more efficient than individuals striking agreements with each other. Shirky’s argument is that the lowering of coordination costs to practically zero through social tools like forums, emails, and blogs make it possible for new loosely structured groups to form outside traditional organisations. Hence the Coasean Floor of transactional costs are lowered, making it efficient and cost effective for such groups to form.

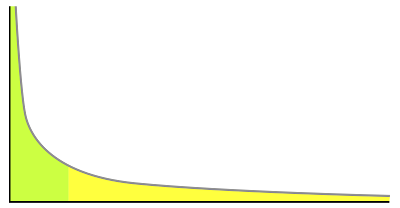

Another example frequently cited by Shirky is the now ubiquitous Power Law or Pareto Principle (80/20 rule), which explained why a tiny group of Flickr users, Wikipedia contributors, or Twitterers contribute a disproportionately large amount of content while the majority provides just one or two contributions. The most famous example of this is Chris Anderson’s Long Tail which describes (according to Wikipedia) that “given a large enough availability of choice, a large population of customers, and negligible stocking and distribution costs, the selection and buying pattern of the population results in a power law distribution curve, or Pareto distribution“. You can see an example of this below:

Effects of the Long-Tail (Courtesy of Hay Kranen)

Covering the various dimensions of group formation from sharing to cooperation, collaboration and ultimately collective action, Here Comes Everybody provides a useful insight into the human psyche and how the availability of social tools help to accelerate latent behaviours.

Unlike other purveyors of social media snake oil, Shirky doesn’t merely offer the positives, and was quite unabashed in proclaiming that the majority of groups will fail. However, because the cost of failure is now free (mediated by the plunging costs of social technologies), one could now embark on “riskier” experiments without having to sell house, home or factory.

Shirky was forthright in declaring that while social technology tools can bring out the best in us, it may also bring about the worst in us. For example, terrorist cells can now form and disband easily without leaving a trace online. This reminded me of A Tale of Two Cities – “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

Examples of group collaboration are plentiful. They range from the tagging of photographs on Flickr for New York’s Mermaid Parade, contribution of articles on Wikipedia (eg Asphalt, which started with a seven word sentence and ended with two fully developed articles), the use of Twitter by political revolutionaries in Egypt, and how forums and blogs help passengers to how Meetups are especially popular with Stay At Home Moms (SAHMs). It was interesting to read that mobilised group actions like flash mobs could be used not only for trivial reasons but rather serious ones too – for example in overthrowing the Belarusian government by eating ice cream! Many of the stories were inspirational and spoke of the promises rather than perils of the social web.

The core of Shirky’s ideas on group forming can probably be boiled down to three simple steps – Promise, Tool and Bargain.

The promise creates the basic premise for one to participate in a group activity, and looks at issues like interests, values and some degree of specificity.

The tools are the platforms, electronic or otherwise, which help to grease the group forming machinery, and they provide the means for one to reach and communicate with another.

The bargain asks the question “What’s In it For Me?” and identifies the social contracts – whether written or unwritten – which underpin such relationships. If this understanding is breached, the end result could lead to the deterioration and destruction of the group – what Shirky termed the Tragedy of the Commons where individuals act on their own self-interests leading to the destruction of a shared limited resource.

In conclusion, I would say that the book provides a useful glimpse of the myriad possibilities in group action presented by the social web and mobile technologies. While it isn’t prescriptive, it does open up one’s mind on the opportunities which exist in leveraging on social technologie to further an agenda.

deep insights!