Courtesy of Management Pocketbooks

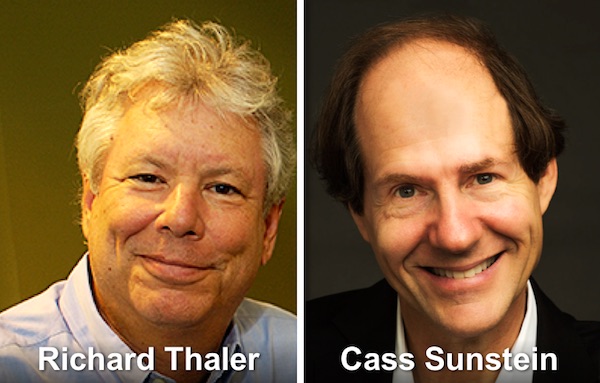

Congratulations to Richard Thaler for winning the Nobel Prize for Economics!

I’m glad that his ideas in behavioural insights have shaped how governments operate – including ours here in Singapore.

In a world that tends to swing to extremes, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book Nudge proposed a radical approach which looks at embracing a middle road to making better decisions.

What is a Nudge?

So what is the meaning of a nudge? According to the book, a nudge can be defined as follows:

A nudge… is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.

According to the authors, nudges are not mandates. They are not laws or rules or commandments.

As an example, putting fruits at the eye level in supermarket check out counters to encourage people to pick up more of them to live more healthily is a nudge. Banning of junk food altogether is not.

Terming their approach as “libertarian paternalism” – a seeming oxymoron at first glance – Thaler and Sunstein mooted that people are often unable to make good decisions when we lack experience, expert knowledge, or are overcome with inertia.

The remedy involves giving them a gentle push in the right direction.

Insurance Policies

Think for example about the last time you invested in an insurance policy.

- Were you aware of how its terms of premium payments were like compared to others?

- Or the penalties that would be imposed if you were to surrender it early?

- What happens if (touch wood) you are somehow unable to keep the policy going?

To guide your citizens to make the best decisions, a nudge in the right direction by the authorities would be useful.

Buying a Car

As a second example, consider the proposed mileage of your car, and its impact on the environment.

- How would your car compare to similar saloons of the same engine capacity?

- What mileage could you achieve per gallon or per litre of fuel?

- If it was fuel efficient, wouldn’t you appreciate it if somebody calculates that for you?

Applying the right nudges here would help to make the purchase decision easier.

Where can Nudges be Applied?

Laced with plenty of fascinating cases, the book suggested that nudges can apply across a wide range of everyday issues.

They include essential decisions like investing, credit markets, social security, health, and education, as well as controversial topics (eg demolishing the state instituted role of marriages).

Unlike other volumes on behavioral economics which are heavy on theory and storytelling, Nudge provides many useful recommendations and insights. Little wonder then that the recommendations from this book and other related publications from Thaler and Sunstein are adopted by numerous organisations and government agencies around the world.

According to the authors, humans are prone to making decisions almost unthinkingly. We allow our autonomous nervous system (aka the Automatic System) to make decisions on our behalf, bypassing the conscious thinking process embedded in our Reflective System.

What happens then when choices become overly complicated? Well, we bail out from deciding altogether, or make random choices.

This happened in the US with their infamously complicated healthcare plans which offered a bewildering range of choices, resulting in the public making less than ideal choices.

6 Principles of Nudge

To circumvent this, public and private sector organisations could do well to develop positive choice architectures.

The mnemonic used in the development of good choice architectures is NUDGES, and it comprises six key principles:

iNcentives

Provide the right incentives for the right people to enable good decision making processes. This should go beyond monetary and material incentives to include other psychological benefits (eg peace of mind).

For governments, this should benefit the population rather than stakeholders with vested interests.

Understand mappings

This looks at how people can better relate to the consequences of different decision pathways. One such approach is termed RECAP: Record, Evaluate, and Compare Alternative Prices.

Citing the example of mobile phone markets, the authors suggested that governments should not regulate how much telcos charge for services. Instead, they should regulate their disclosure practices.

By doing so, they will make it easier for customers to compare what they are truly paying for, and ensure that all hidden fees are exposed.

Defaults

Defaults are “ubiquitous and powerful.” People often leave the default decision on if they are too lazy to make a decision.

Increasingly, online platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, and Google are using defaults to nudge people to take action. Such defaults come in the form of pre-written scripts and prompts triggered by algorithms that are powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI) engines.

What about governments?

Well, policy makers can ensure that their default position would be one that benefits as many people as possible. This is preferred to giving their citizens a “zero” choice which opts out completely from beneficial programmes.

Give feedback

A good way to help humans (whom the authors term as people who don’t just decide based on reason and logic) improve their performance is to provide feedback.

An example is the development of a fake “shutter click” sound on digital cameras which lets people know that a photograph is taken. Or the flashing of an “in progress” screen showing movement when you’re waiting for an app to complete its action.

Expect error

To err is human and forgive divine. Unfortunately, few humans can follow instructions down to a T.

To allow for this, designs should be made such that people are forewarned before a more disastrous outcome happens. An example is the design of drug taking – once in the morning after breakfast for instance, is better than 3 times a day.

Structure complex choices

When choices become too abundant, people tend to find ways to simplify them and break them down. Good choice architecture will find ways to make this more evident for people.

An example cited was the choice of paint. Instead of using words like “Roasted Sesame Seed” or “Kansas Grain,” consider arranging similar colour themes next to each other. This could help people to choose the right shades and hues.

Conclusion

Overall, the book provided much food for thought. Its emphasis on a “Third Way” was certainly refreshing.

By allowing people some freedom while egging them towards a more beneficial option when the need arises, nudges help to improve how the world functions in many different areas. This can be achieved without going to the extremes of complete freedom or complete paternalism.

Admittedly, this is going to be difficult to apply, especially for private enterprises driven towards self-serving profitability. However, it may just be the approach needed by both the public and the people (non-profit) sectors.

3 Comments