GrabCar and Uber has disrupted taxis in Singapore and around the world (Courtesy of GrabCar)

Have you wondered how innovations can be “disruptive”? Or why entire industries can be wiped out with new entrants?

Last night, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong spoke about the impact of disruptive innovations during the National Day Rally Speech.

In his speech, he mentioned how new players to Singapore’s market like e-commerce retailers and car hire companies Uber and GrabCar were disrupting incumbents like brick-and-mortar retailers and traditional taxi companies.

(This was the same speech where he had to pause halfway due to ill-health – thankfully our PM recovered and was alright thereafter.)

More than three years ago, I read Clayton Christensen’s epic business bestseller The Innovator’s Dilemma and was blown away by its brilliance. Focused on the topic of radical innovations, the book helped me to understand how disruptions could emerge in any industry.

What Are Disruptive Innovations?

Backed by rigorous research, Christensen’s premise was that well-managed companies that watch competitors, listen to customers, and invest heavily in new technologies can still lose market dominance.

The reason? Disruptive innovations.

Contrary to popular belief, a disruptive technology or innovation isn’t the latest, most cutting-edge or radical invention. Rather, disruptive innovations can be defined as follows:

Disruptive Innovations: a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors. – Clayton Christensen

The humble beginnings of disruptive innovations contrasts significantly with sustaining innovations developed to provide better value to existing markets. Sustaining innovations are akin to the continuous improvement methodology favoured by Deming and the Japanese innovators.

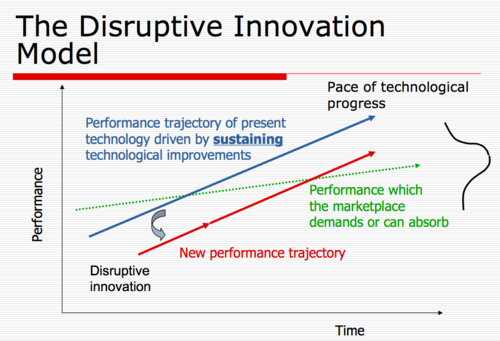

This can be visualised by the chart below:

Courtesy of Lubor on Tech

A disruptive innovation creates a new value network. This is defined by Investopedia as “a set of connections between organizations and/or individuals interacting with each other to benefit the entire group” in an emerging market.

As the speed of technological advancements out paces customer expectations, this new innovation eventually moves upstream to “disrupt” a higher value, larger and more mature market.

Note that disruptive innovations aren’t necessarily revolutionary or transformative. They normally start out being simpler, cheaper, more reliable or convenient than established ones. Initially, these technologies are unable to meet the minimal needs of existing markets. Over time however, they can supplant sustaining technologies with other competitive variables once the performance hurdle is crossed.

This idea can be represented by the diagram below:

Courtesy of Bikewriter.com

Using detailed examples from the disk drive, mechanical excavator, steel milling and retail industries, The Innovator’s Dilemma provided compelling scenarios for businesses to think differently about innovation.

Key lessons from these case studies are summarised by the following principles of disruptive innovation:

Principle #1: Companies Depend on Customers and Investors for Resources

The theory of resource dependence stipulates that existing customers and shareholders ultimately dictate where funds, manpower and other resources are channeled to.

Thus, managers in a large mainstream organisation may find it difficult to justify pumping in human or financial resources to smaller new markets where disruptive technologies first emerge. This principle is highly evident amongst many traditional businesses like brick and mortar retail, media conglomerates, and transport companies.

Principle #2: Small Markets Don’t Solve the Growth Needs of Large Companies

Disruptive technologies normally lead to the growth of small and nascent emerging markets.

Unfortunately, such markets are usually not “large enough to be interesting” and cannot meet the needs of large companies to grow their market, maintain share prices (via quarterly growth forecasts) or provide adequate opportunities for employees to grow. Thus, they often get ignored by incumbents.

Principle #3: Markets that Don’t Exist Can’t Be Analysed

As emerging markets are highly unpredictable, traditional market research and planning activities are ill-suited to forecast them accurately.

Unlike sustaining technologies, markets created by disruptive technologies require a discovery based planning approach. Here, managers assume that forecasts are wrong (rather than right) and develop iterative plans for learning and testing.

This principle is later popularised by Eric Ries’ The Lean Startup which looks at developing a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) to be market-tested in an experimental and iterative approach.

Principle #4: An Organisation’s Capabilities Define Its Disabilities

Organisational capabilities are embedded in its processes, values and culture. These are often fairly rigid as they are formulated to achieve very specific purposes in an efficient and effective manner. They are also more than the sum of the capabilities of its employees.

A process that is effective at managing and selling a luxury car (eg Mercedes E Class), for example, may not be effective for smaller urban vehicles. Similarly, a process whereby incumbents are efficient in serving customers from a physical location may be difficult to pivot to one which involves the delivery of products and services to their locations.

Principle #5: Technology Supply May Not Equal Market Demand

As earlier mentioned, disruptive technologies in emerging markets eventually become fully performance-competitive in mainstream markets. This is because the rate of technological progress in products leapfrogs the rate of performance improvements mainstream customers demand or can absorb.

Put it simply, the improvements in technology are so fast that they rapidly exceed expectations of mainstream customers. A case in point are the laptop computers with blindingly fast speeds and massive capacities.

Once this happens, the basis of product choice evolves from functionality to reliability, then convenience, and ultimately price (that’s also when it becomes commodified). A case in point is seen in how consumers veer towards Uber/GrabCar rather than traditional taxi companies.

This can be represented by the chart below:

Courtesy of Alec Saunders

Responding to Disruptive Technologies

Against this backdrop, how should managers in incumbent companies act? Here, Christensen proposes the following:

1) Give responsibility for disruptive technologies to new organisations serving new customers that need them. This would then allow adequate resources to be apportioned to emerging markets.

2) Set up a separate organisation away from the mainstream organisation. One which is small enough to be excited about the initial modest gains in sales, profitability and market share.

3) Plan for failure and learning. Hedge small bets on commercialising disruptive technologies and make rapid revisions as data on customer needs and market responses are obtained. Adopt the Lean Startup methodology.

4) Rely less on technological breakthroughs and more on discovering new markets outside current mainstream markets. By doing so, you may find that the very attributes which make disruptive technologies unattractive to mainstream markets are those from which new markets can be built.

The Case for Electric Cars

Towards the end of the book, Christensen elaborated on a hypothetical case study of the electric car and how the principles of disruptive innovation could be applied.

His ideas include creating a different distribution network (sell cars in consumer electronic stores), designing for crowded Asian cities (rather than sprawling Western ones), and emphasising simplicity and convenience (as opposed to performance). Following his arguments on the need for existing automakers to think of new markets rather than serve the old, I couldn’t help nodding my head in agreement.

Overall, The Innovator’s Dilemma is a “must read” for business leaders, managers and entrepreneurs keen to make an impact. It’s central thesis of searching new markets for disruptive innovations (as opposed to shoehorning them to current customers) is a novel idea worthy of consideration.

Special thanks to Belinda Ang for the review copy!

3 Comments